Inside cc1¶

GCC is a collection of compilers for different languages, which can generate code for a wide variety of different CPU architectures.

GCC currently supports 10 source languages, and 55 target CPU architectures. We don’t want to have to write 550 different compilers, so, as is common, GCC is structured into three parts:

source language “front ends” - one for each source language, taking the source language as input, using it to generating an “intermediate represention” (IR) of the user’s code in a language-independent internal format

target-specific “back ends” - one for each target, taking the intermediate representation as input, and generating assembler for that target

the so-called “middle end”, sitting between these, which optimizes the code, so that the back end has better code to work with

So cc1 built for x86_64 has the C frontend, the shared

optimizing code, and the x86_64 backend:

+-----+

+-| cc1 |--------------------------------------------------+

| +-----+ |

| |

| C frontend Optimizer x86_64 backend |

C source ====+==============> IR =============> IR ===================+==> x86_64 asm

| |

+----------------------------------------------------------+

Sadly the above picture is an idealized picture, in that the code is rather messier than that in practice. It’s also over-simplified, in that GCC actually has several intermediate representations, which we’ll talk about in detail below.

if you’re interested in adding new warnings to GCC, you’ll probably want to just look at the frontends for now, and to merely skim the sections below.

if you want to make GCC generate better code, you’ll want to look at the middle-end and backends, and find out more about gcc’s intermediate representations by reading the section below

if you’re interested in adding support to GCC for a new kind of CPU, you’ll want to look mostly at the backend/RTL sections below

How does cc1 turn C into assembler?¶

When figuring out how the compiler works, it’s best to start with a really

simple source file - in particular, one with doesn’t #include any

header files. Our earlier example used <stdio.h>, so let’s make

an even simpler test.c:

int test (int a, int b, int c, int d)

{

if (a)

return (b - c) * d;

else

return (c - b) * d;

}

Compiling it to assembler, with some optimization (-O2) and

enabling verbose assembler output (-fverbose-asm):

$ gcc -S test.c -O2 -fverbose-asm

gives this test.s:

.file "test.c"

; ...omitting dump of options for brevity...

.text

.p2align 4

.globl test

.type test, @function

test:

.LFB0:

.cfi_startproc

# test.c:2: {

movl %ecx, %eax # tmp97, d

# test.c:3: if (a)

testl %edi, %edi # tmp94

je .L2 #,

# test.c:4: return (b - c) * d;

subl %edx, %esi # c, tmp89

# test.c:4: return (b - c) * d;

imull %esi, %eax # tmp89, <retval>

ret

.p2align 4,,10

.p2align 3

.L2:

# test.c:6: return (c - b) * d;

subl %esi, %edx # b, tmp90

# test.c:6: return (c - b) * d;

imull %edx, %eax # tmp90, <retval>

# test.c:7: }

ret

.cfi_endproc

.LFE0:

.size test, .-test

.ident "GCC: (GNU) 10.3.1 20210422 (Red Hat 10.3.1-1)"

.section .note.GNU-stack,"",@progbits

where cc1 has converted the C code into a pair of

subtractions (subl), and a pair of multiplies (imull)

that populate the %eax register, used for the return value.

You can see GCC’s intermediate representations using GCC’s dump options. If

we add -fdump-tree-all -fdump-ipa-all -fdump-rtl-all to the

above command line, giving:

gcc -S test.c -O2 -fverbose-asm -fdump-tree-all -fdump-ipa-all -fdump-rtl-all

then these dump options lead cc1 to emit many dump files (192 in the following example):

$ ls

test.c test.c.101t.alias test.c.238r.vregs

test.c.000i.cgraph test.c.102t.retslot test.c.239r.into_cfglayout

test.c.000i.ipa-clones test.c.103t.fre3 test.c.240r.jump

test.c.000i.type-inheritance test.c.104t.mergephi2 test.c.241r.subreg1

test.c.004t.original test.c.105t.thread1 test.c.242r.dfinit

test.c.005t.gimple test.c.106t.vrp1 test.c.243r.cse1

test.c.007t.omplower test.c.107t.dce2 test.c.244r.fwprop1

test.c.008t.lower test.c.108t.stdarg test.c.245r.cprop1

test.c.011t.eh test.c.109t.cdce test.c.246r.pre

test.c.013t.cfg test.c.110t.cselim test.c.248r.cprop2

test.c.015t.ompexp test.c.111t.copyprop1 test.c.251r.ce1

test.c.018i.visibility test.c.112t.ifcombine test.c.252r.reginfo

test.c.019i.build_ssa_passes test.c.113t.mergephi3 test.c.253r.loop2

test.c.020t.fixup_cfg1 test.c.114t.phiopt2 test.c.254r.loop2_init

test.c.021t.ssa test.c.115t.tailr2 test.c.255r.loop2_invariant

test.c.023t.nothrow test.c.116t.ch2 test.c.258r.loop2_done

test.c.024i.opt_local_passes test.c.117t.cplxlower1 test.c.261r.cprop3

test.c.025t.fixup_cfg2 test.c.118t.sra test.c.262r.stv1

test.c.026t.local-fnsummary1 test.c.119t.thread2 test.c.263r.cse2

test.c.027t.einline test.c.120t.dom2 test.c.264r.dse1

test.c.028t.early_optimizations test.c.121t.copyprop2 test.c.265r.fwprop2

test.c.029t.objsz1 test.c.122t.isolate-paths test.c.267r.init-regs

test.c.030t.ccp1 test.c.123t.dse2 test.c.268r.ud_dce

test.c.031t.forwprop1 test.c.124t.reassoc1 test.c.269r.combine

test.c.032t.ethread test.c.125t.dce3 test.c.271r.stv2

test.c.033t.esra test.c.126t.forwprop3 test.c.272r.ce2

test.c.034t.ealias test.c.127t.phiopt3 test.c.273r.jump_after_combine

test.c.035t.fre1 test.c.128t.ccp3 test.c.274r.bbpart

test.c.036t.evrp test.c.129t.sincos test.c.275r.outof_cfglayout

test.c.037t.mergephi1 test.c.130t.bswap test.c.276r.split1

test.c.038t.dse1 test.c.131t.laddress test.c.277r.subreg3

test.c.039t.cddce1 test.c.132t.lim2 test.c.279r.mode_sw

test.c.040t.phiopt1 test.c.133t.walloca2 test.c.280r.asmcons

test.c.041t.tailr1 test.c.134t.pre test.c.285r.ira

test.c.042t.switchconv test.c.135t.sink test.c.286r.reload

test.c.044t.profile_estimate test.c.139t.dce4 test.c.288r.postreload

test.c.045t.local-pure-const1 test.c.140t.fix_loops test.c.290r.split2

test.c.046t.fnsplit test.c.171t.no_loop test.c.291r.ree

test.c.047t.release_ssa test.c.174t.veclower21 test.c.292r.cmpelim

test.c.048t.local-fnsummary2 test.c.175t.switchlower1 test.c.293r.pro_and_epilogue

test.c.049i.remove_symbols test.c.177t.reassoc2 test.c.294r.dse2

test.c.061i.targetclone test.c.178t.slsr test.c.295r.csa

test.c.065i.free-fnsummary1 test.c.181t.fre4 test.c.296r.jump2

test.c.071i.whole-program test.c.182t.thread3 test.c.297r.compgotos

test.c.072i.profile_estimate test.c.183t.dom3 test.c.299r.peephole2

test.c.073i.icf test.c.184t.strlen1 test.c.300r.ce3

test.c.074i.devirt test.c.185t.thread4 test.c.302r.cprop_hardreg

test.c.075i.cp test.c.186t.vrp2 test.c.303r.rtl_dce

test.c.076i.sra test.c.187t.copyprop5 test.c.304r.bbro

test.c.079i.fnsummary test.c.188t.wrestrict test.c.305r.split3

test.c.080i.inline test.c.189t.dse3 test.c.306r.sched2

test.c.081i.pure-const test.c.190t.cddce3 test.c.308r.stack

test.c.082i.free-fnsummary2 test.c.191t.forwprop4 test.c.309r.alignments

test.c.083i.static-var test.c.192t.phiopt4 test.c.311r.mach

test.c.084i.single-use test.c.193t.fab1 test.c.312r.barriers

test.c.085i.comdats test.c.194t.widening_mul test.c.317r.shorten

test.c.086i.materialize-all-clones test.c.195t.store-merging test.c.318r.nothrow

test.c.088i.simdclone test.c.196t.tailc test.c.319r.dwarf2

test.c.089t.fixup_cfg3 test.c.197t.dce7 test.c.320r.final

test.c.094t.ccp2 test.c.198t.crited1 test.c.321r.dfinish

test.c.096t.cunrolli test.c.200t.uncprop1 test.c.322t.statistics

test.c.097t.backprop test.c.201t.local-pure-const2 test.c.323t.earlydebug

test.c.098t.phiprop test.c.234t.nrv test.c.324t.debug

test.c.099t.forwprop2 test.c.235t.optimized test.s

test.c.100t.objsz2 test.c.237r.expand

You’ll see that they’re of the form test.c. followed by a

3 digit number, followed by “t”, “i”, or “r”, then a suffix.

The precise numbering and suffixes of dump files varies from release to

release of GCC, and the subset that gets emitted will vary depending on

the optimization option you choose - there were 192 in the above example

(GCC 10, with -O2).

The dump files show the state of GCC’s intermediate representation of the

code at each “optimization pass”. The numbering roughly corresponds to a

time-ordering of the states within the compiler, so that e.g.

test.c.004t.original shows the initial state of the IR coming

out of the C frontend, whilst test.c.320r.final shows the

final state as assembler is written out. Beware, though that the “i”

dumps are numbered out-of-order relative to the other “t” and “r” passes.

At a high level, cc1 works as follows.

Lexing¶

First the input source is “tokenized”, so that the stream of input characters is divided into a stream of tokens. This is called “lexing”, and largely implemented in gcc in libcpp (which also implements the preprocessor - hence the name) so that e.g. we go from the sequence of characters:

return (b - c) * d;

to the sequence of tokens:

CPP_KEYWORD(RID_RETURN) CPP_OPEN_PAREN CPP_NAME("b") CPP_MINUS CPP_NAME("c") CPP_CLOSE_PAREN CPP_MULT CPP_NAME("d") CPP_SEMICOLON

annotated with information about where in the user’s source they occurred.

Parsing and the tree type¶

Next the frontend parses the tokens from a flat stream into a tree-like

structure reflecting the grammar of the language (or complains about

syntax errors or type errors, and bails out). Most warnings are

implemented here, so if you’re interested in adding new warnings, this

is the place to look. This stage uses gcc’s tree type.

There may be frontend-specific kinds of node, in the tree but the

frontend will convert these to a generic form,

so that after each frontend the middle end “sees” a tree

representation that we call

generic

(unless the frontend gave up due to a sufficiently serious error in the

user’s code).

You can see the “generic” representation in the

test.c.004t.original dump:

;; Function test (null)

;; enabled by -tree-original

{

if (a != 0)

{

return (b - c) * d;

}

else

{

return (c - b) * d;

}

}

In this example, the dump of the tree IR closely resembles the original C code, but sometimes you will see control flow expressed via “goto” statements that go to numbered labels, and temporary variables introduced by the frontend.

If we’re running under the debugger (see Debugging GCC), we can see the tree for a function body like this:

(gdb) call debug_tree(fndecl->function_decl.saved_tree)

<bind_expr 0x7fffea3f6240

type <void_type 0x7fffea2bdf18 void VOID

align:8 warn_if_not_align:0 symtab:0 alias-set -1 canonical-type 0x7fffea2bdf18

pointer_to_this <pointer_type 0x7fffea2c5000>>

side-effects

body <cond_expr 0x7fffea3f6210 type <void_type 0x7fffea2bdf18 void>

side-effects

arg:0 <ne_expr 0x7fffea3d0d20 type <integer_type 0x7fffea2bd5e8 int>

arg:0 <parm_decl 0x7fffea3f8000 a>

arg:1 <integer_cst 0x7fffea2c2078 constant 0>

test.c:3:7 start: test.c:3:7 finish: test.c:3:7>

arg:1 <return_expr 0x7fffea3e30e0 type <void_type 0x7fffea2bdf18 void>

side-effects

arg:0 <modify_expr 0x7fffea3d0d98 type <integer_type 0x7fffea2bd5e8 int>

side-effects arg:0 <result_decl 0x7fffea2b1a50 D.1934>

arg:1 <mult_expr 0x7fffea3d0d70 type <integer_type 0x7fffea2bd5e8 int>

arg:0 <minus_expr 0x7fffea3d0d48 type <integer_type 0x7fffea2bd5e8 int>

arg:0 <parm_decl 0x7fffea3f8080 b> arg:1 <parm_decl 0x7fffea3f8100 c>

test.c:4:15 start: test.c:4:12 finish: test.c:4:18> arg:1 <parm_decl 0x7fffea3f8180 d>

test.c:4:20 start: test.c:4:12 finish: test.c:4:22>

test.c:4:20 start: test.c:4:12 finish: test.c:4:22>

test.c:4:20 start: test.c:4:12 finish: test.c:4:22>

arg:2 <return_expr 0x7fffea3e3100 type <void_type 0x7fffea2bdf18 void>

side-effects

arg:0 <modify_expr 0x7fffea3d0e38 type <integer_type 0x7fffea2bd5e8 int>

side-effects arg:0 <result_decl 0x7fffea2b1a50 D.1934>

arg:1 <mult_expr 0x7fffea3d0e10 type <integer_type 0x7fffea2bd5e8 int>

arg:0 <minus_expr 0x7fffea3d0de8 type <integer_type 0x7fffea2bd5e8 int>

arg:0 <parm_decl 0x7fffea3f8100 c> arg:1 <parm_decl 0x7fffea3f8080 b>

test.c:6:15 start: test.c:6:12 finish: test.c:6:18> arg:1 <parm_decl 0x7fffea3f8180 d>

test.c:6:20 start: test.c:6:12 finish: test.c:6:22>

test.c:6:20 start: test.c:6:12 finish: test.c:6:22>

test.c:6:20 start: test.c:6:12 finish: test.c:6:22>

test.c:3:6 start: test.c:3:6 finish: test.c:3:6>

block <block 0x7fffea3d8420 used

supercontext <function_decl 0x7fffea3d5500 test type <function_type 0x7fffea3dd1f8>

public static QI test.c:1:5 align:8 warn_if_not_align:0 context <translation_unit_decl 0x7fffea2b1ac8 test.c> initial <block 0x7fffea3d8420> result <result_decl 0x7fffea2b1a50 D.1934> arguments <parm_decl 0x7fffea3f8000 a>

struct-function 0x7fffea3f9000>>

test.c:2:1 start: test.c:2:1 finish: test.c:2:1>

where for example:

cond_expr is the conditional expression, with three arguments:

ne_expr is a “not-equal expression” for

a != 0each return_expr is one of the two return expressions

parm_decl is a parameter declaration (such as

a)integer_cst is an integer constant (as opposed to a cast), such as

0

gimple¶

The tree-based IR can contain arbitrarily-complicated nested expressions, which is relatively easy for the frontends to generate, but difficult for the optimizer to work with, so GCC almost immediately converts it into a form named “gimple”, in which compound expressions such as:

(b - c) * d

get flattened into a series of assignments to temporary variables. We

can see the initial form of the gimple in the test.c.005t.gimple

dump:

test (int a, int b, int c, int d)

{

int D.1938;

if (a != 0) goto <D.1936>; else goto <D.1937>;

<D.1936>:

_1 = b - c;

D.1938 = d * _1;

// predicted unlikely by early return (on trees) predictor.

return D.1938;

<D.1937>:

_2 = c - b;

D.1938 = d * _2;

// predicted unlikely by early return (on trees) predictor.

return D.1938;

}

Note how the if/else control flow has become “goto” statements, and how the “gimplifier” has flattened:

(b - c) * d

into assignments to two temporaries (named _1 and D.1938):

_1 = b - c;

D.1938 = d * _1;

This gives us a sequence of gimple statements, some of which are labels,

and some of which goto those labels.

The official documentation on gimple is here.

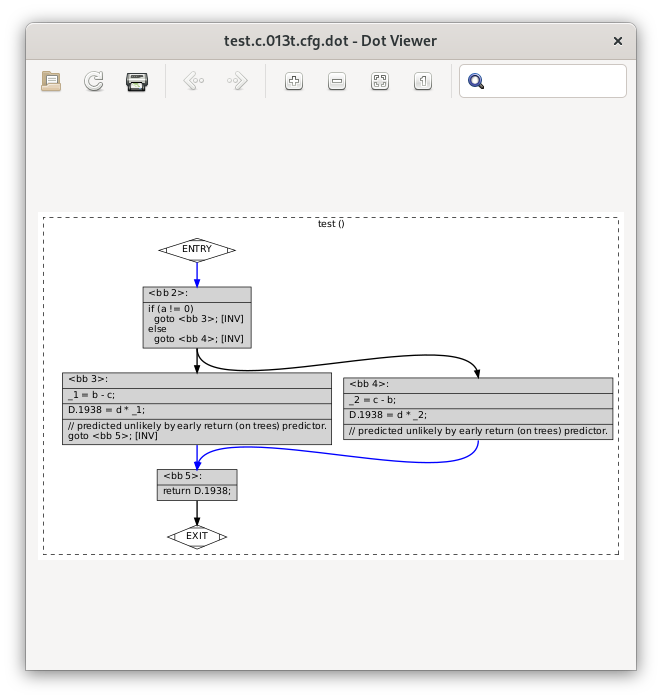

gimple with a CFG¶

Although some optimization passes do work on this “gimple with labels”

representation, it is almost immediately converted to a Control Flow

Graph (CFG), a directed graph of “basic blocks” - sequences of

statements with no control flow, where the control flow is expressed

as the edges between the basic blocks. This can be seen in the

test.c.013t.cfg dump:

;; Function test (test, funcdef_no=0, decl_uid=1933, cgraph_uid=1, symbol_order=0)

;; 1 loops found

;;

;; Loop 0

;; header 0, latch 1

;; depth 0, outer -1

;; nodes: 0 1 2 3 4 5

;; 2 succs { 3 4 }

;; 3 succs { 5 }

;; 4 succs { 5 }

;; 5 succs { 1 }

test (int a, int b, int c, int d)

{

int D.1938;

<bb 2> :

if (a != 0)

goto <bb 3>; [INV]

else

goto <bb 4>; [INV]

<bb 3> :

_1 = b - c;

D.1938 = d * _1;

// predicted unlikely by early return (on trees) predictor.

goto <bb 5>; [INV]

<bb 4> :

_2 = c - b;

D.1938 = d * _2;

// predicted unlikely by early return (on trees) predictor.

<bb 5> :

return D.1938;

}

You can see the basic blocks via e.g. the <bb 2> headers.

There is also now a single return statement from the function; the

multiple return statements are now all expressed by assigning to a

temporary (D.1938), and then a goto to the basic block

containing the return statement.

If you add the -graph suffix to the dump command line options:

$ gcc -S test.c -O2 -fverbose-asm \

-fdump-tree-all-graph -fdump-ipa-all-graph -fdump-rtl-all-graph

then in addition to the dump files listed above, cc1 will

also generate .dot files, suitable for use with GraphViz.

My favorite .dot file viewer is

xdot, which shows

test.c.013t.cfg.dot as follows:

which makes it easy to see the individual basic blocks, the statements within them, and the control flow linking them.

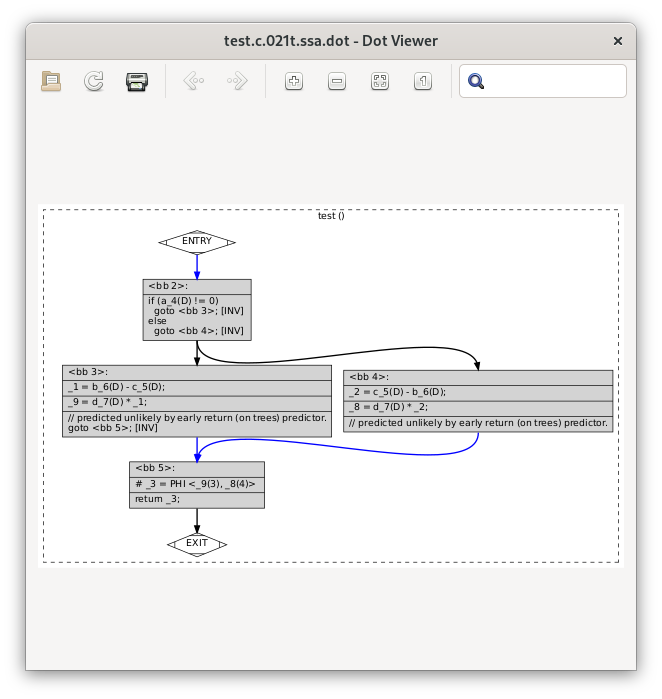

gimple-SSA¶

After a few more optimization passes, the gimple-cfg IR is then converted to Static Single Assignment form (SSA). SSA form is commonly used inside compilers, as it makes many kinds of optimization much easier to implement. In SSA, every local variable is only ever assigned to once; if there are multiple assignments to a local variable, it gets split up into multiple versions.

In our example, you can see the SSA form of the IR in test.c.021t.ssa:

;; Function test (test, funcdef_no=0, decl_uid=1933, cgraph_uid=1, symbol_order=0)

test (int a, int b, int c, int d)

{

int _1;

int _2;

int _3;

int _8;

int _9;

<bb 2> :

if (a_4(D) != 0)

goto <bb 3>; [INV]

else

goto <bb 4>; [INV]

<bb 3> :

_1 = b_6(D) - c_5(D);

_9 = d_7(D) * _1;

// predicted unlikely by early return (on trees) predictor.

goto <bb 5>; [INV]

<bb 4> :

_2 = c_5(D) - b_6(D);

_8 = d_7(D) * _2;

// predicted unlikely by early return (on trees) predictor.

<bb 5> :

# _3 = PHI <_9(3), _8(4)>

return _3;

}

and (in dot form) as test.c.021t.ssa.dot:

You can see that the single temporary D.1938 from the earlier form

of the IR has been split into three separate temporaries, where the two

assignments:

D.1938 = d * _1;

and:

D.1938 = d * _2;

have now become these two assignments to separate temporaries:

_9 = d_7(D) * _1;

and:

_8 = d_7(D) * _2;

and at the point where control flow merges, we have a special construct

called a “phi node” which assigns to the new temporary _3 from either

one of the _9 or _8, depending on whether control flow came

from block 3 or block 4:

# _3 = PHI <_9(3), _8(4)>

You can see that the parameters b and c from the earlier form

of the IR have also been numbered, so that the SSA form captures e.g.

that we’re accessing b_6(D), meaning version 6 of parameter b,

where the (D) means the initial value at the function entry: if

code wrote to one of these parameters, the SSA form would have a

different numbered version of it after the write.

The official documentation for GCC’s gimple-ssa form is here.

Once we’re in gimple-SSA form, there are almost 200 optimization passes, which can be roughly divided into:

“intraprocedural” passes. These work on one function at a time. They have a “t” code in their dump file. For example,

test.c.175t.switchloweris the dump file for an optimization pass which converts gimpleswitchstatements into lower-level gimple statements and control flow (which doesn’t do anything in our example above, as it doesn’t have any switch statements; try writing a simple C source file with a switch statement and see what it does)“interprocedural passes” which consider all of the functions at once, such as which functions call which other functions. These have an “i” code in their dump file. An example is

test.c.080i.inlinethough given that our example has only one function, the interprocedural passes won’t do anything useful

The full set of optimizations passes can be see in GCC’s source tree in the file gcc/passes.def

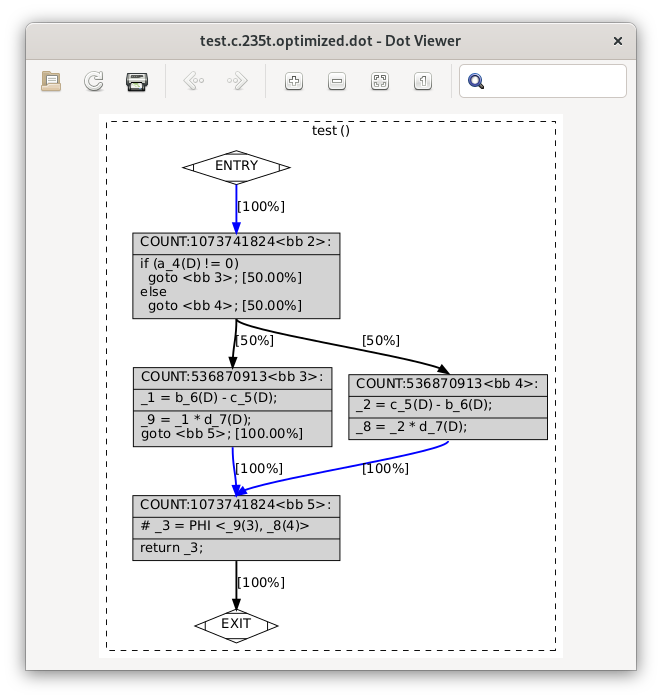

After about 200 gimple optimizations passes, we’re done with the

gimple-SSA form; its final state can be seen in test.c.235t.optimized:

;; Function test (test, funcdef_no=0, decl_uid=1933, cgraph_uid=1, symbol_order=0)

test (int a, int b, int c, int d)

{

int _1;

int _2;

int _3;

int _8;

int _9;

<bb 2> [local count: 1073741824]:

if (a_4(D) != 0)

goto <bb 3>; [50.00%]

else

goto <bb 4>; [50.00%]

<bb 3> [local count: 536870913]:

_1 = b_6(D) - c_5(D);

_9 = _1 * d_7(D);

goto <bb 5>; [100.00%]

<bb 4> [local count: 536870913]:

_2 = c_5(D) - b_6(D);

_8 = _2 * d_7(D);

<bb 5> [local count: 1073741824]:

# _3 = PHI <_9(3), _8(4)>

return _3;

}

and test.c.235t.optimized.dot:

For our simple example, this hasn’t been changed much since the initial conversion to SSA form; it’s gained some estimates about how many times each basic block will be run (in lieu of real profiling data).

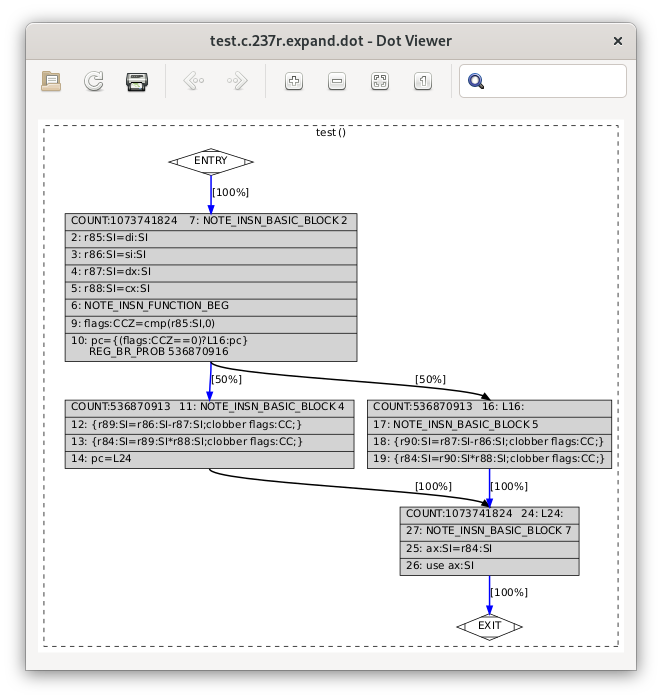

RTL¶

At this point, the gimple is converted to Register Transfer Language

(RTL), a much lower-level representation of the code, which will allow

us to eventually go all the way to assembler. The conversion happens

in an optimization pass called “expand”; we can see the initial RTL form

of the code in the test.c.237r.expand dump file:

;; Function test (test, funcdef_no=0, decl_uid=1933, cgraph_uid=1, symbol_order=0)

;; Generating RTL for gimple basic block 2

;; Generating RTL for gimple basic block 3

;; Generating RTL for gimple basic block 4

;; Generating RTL for gimple basic block 5

try_optimize_cfg iteration 1

Merging block 3 into block 2...

Merged blocks 2 and 3.

Merged 2 and 3 without moving.

Redirecting jump 14 from 6 to 7.

Merging block 6 into block 5...

Merged blocks 5 and 6.

Merged 5 and 6 without moving.

Removing jump 22.

try_optimize_cfg iteration 2

;;

;; Full RTL generated for this function:

;;

(note 1 0 7 NOTE_INSN_DELETED)

(note 7 1 2 2 [bb 2] NOTE_INSN_BASIC_BLOCK)

(insn 2 7 3 2 (set (reg/v:SI 85 [ a ])

(reg:SI 5 di [ a ])) "test.c":2:1 -1

(nil))

(insn 3 2 4 2 (set (reg/v:SI 86 [ b ])

(reg:SI 4 si [ b ])) "test.c":2:1 -1

(nil))

(insn 4 3 5 2 (set (reg/v:SI 87 [ c ])

(reg:SI 1 dx [ c ])) "test.c":2:1 -1

(nil))

(insn 5 4 6 2 (set (reg/v:SI 88 [ d ])

(reg:SI 2 cx [ d ])) "test.c":2:1 -1

(nil))

(note 6 5 9 2 NOTE_INSN_FUNCTION_BEG)

(insn 9 6 10 2 (set (reg:CCZ 17 flags)

(compare:CCZ (reg/v:SI 85 [ a ])

(const_int 0 [0]))) "test.c":3:6 -1

(nil))

(jump_insn 10 9 11 2 (set (pc)

(if_then_else (eq (reg:CCZ 17 flags)

(const_int 0 [0]))

(label_ref 16)

(pc))) "test.c":3:6 -1

(int_list:REG_BR_PROB 536870916 (nil))

-> 16)

(note 11 10 12 4 [bb 4] NOTE_INSN_BASIC_BLOCK)

(insn 12 11 13 4 (parallel [

(set (reg:SI 89)

(minus:SI (reg/v:SI 86 [ b ])

(reg/v:SI 87 [ c ])))

(clobber (reg:CC 17 flags))

]) "test.c":4:15 -1

(nil))

(insn 13 12 14 4 (parallel [

(set (reg:SI 84 [ <retval> ])

(mult:SI (reg:SI 89)

(reg/v:SI 88 [ d ])))

(clobber (reg:CC 17 flags))

]) "test.c":4:20 -1

(nil))

(jump_insn 14 13 15 4 (set (pc)

(label_ref:DI 24)) "test.c":4:20 737 {jump}

(nil)

-> 24)

(barrier 15 14 16)

(code_label 16 15 17 5 2 (nil) [1 uses])

(note 17 16 18 5 [bb 5] NOTE_INSN_BASIC_BLOCK)

(insn 18 17 19 5 (parallel [

(set (reg:SI 90)

(minus:SI (reg/v:SI 87 [ c ])

(reg/v:SI 86 [ b ])))

(clobber (reg:CC 17 flags))

]) "test.c":6:15 -1

(nil))

(insn 19 18 24 5 (parallel [

(set (reg:SI 84 [ <retval> ])

(mult:SI (reg:SI 90)

(reg/v:SI 88 [ d ])))

(clobber (reg:CC 17 flags))

]) "test.c":6:20 -1

(nil))

(code_label 24 19 27 7 1 (nil) [1 uses])

(note 27 24 25 7 [bb 7] NOTE_INSN_BASIC_BLOCK)

(insn 25 27 26 7 (set (reg/i:SI 0 ax)

(reg:SI 84 [ <retval> ])) "test.c":7:1 -1

(nil))

(insn 26 25 0 7 (use (reg/i:SI 0 ax)) "test.c":7:1 -1

(nil))

and test.c.237r.expand.dot:

The RTL form of the IR is much closer to assembler: whereas gimple works in terms of variables of specific data types, RTL instructions work in terms of low-level operations on an arbitrary number of registers of specific bit sizes.

There are about 100 RTL optimization passes, which solve problems such as:

implementing function call/return, parameter passing, and the stack of frames, in terms of what actually exists at the CPU level (the “calling conventions” of an ABI)

using the registers actually available on the CPU, rather than blithely assuming that there’s an arbitrary number of registers for every function, a process called register allocation

using the instructions and addressing modes actually available on the CPU, rather than assuming an ideal set of combinations

various optimizations, such as scheduling instructions so that they run efficiently on the target CPU (e.g. handling delay slots)

converting the CFG that RTL inherited from gimple into a flat series of instructions connected by jumps (honoring constraints such as limitations on how many bytes a jump instruction can go)

The official documentation for RTL is here.

The “final” form of RTL¶

Eventually the RTL form is suitable for output in assembler, in an

optimization pass called “final” (which, annoyingly, is no longer the

final pass); the test.c.320r.final dump file looks like this:

;; Function test (test, funcdef_no=0, decl_uid=1933, cgraph_uid=1, symbol_order=0)

test

Dataflow summary:

;; fully invalidated by EH 0 [ax] 1 [dx] 2 [cx] 4 [si] 5 [di] 8 [st] 9 [st(1)] 10 [st(2)] 11 [st(3)] 12 [st(4)] 13 [st(5)] 14 [st(6)] 15 [st(7)] 17 [flags] 18 [fpsr] 20 [xmm0] 21 [xmm1] 22 [xmm2] 23 [xmm3] 24 [xmm4] 25 [xmm5] 26 [xmm6] 27 [xmm7] 28 [mm0] 29 [mm1] 30 [mm2] 31 [mm3] 32 [mm4] 33 [mm5] 34 [mm6] 35 [mm7] 36 [r8] 37 [r9] 38 [r10] 39 [r11] 44 [xmm8] 45 [xmm9] 46 [xmm10] 47 [xmm11] 48 [xmm12] 49 [xmm13] 50 [xmm14] 51 [xmm15] 52 [xmm16] 53 [xmm17] 54 [xmm18] 55 [xmm19] 56 [xmm20] 57 [xmm21] 58 [xmm22] 59 [xmm23] 60 [xmm24] 61 [xmm25] 62 [xmm26] 63 [xmm27] 64 [xmm28] 65 [xmm29] 66 [xmm30] 67 [xmm31] 68 [k0] 69 [k1] 70 [k2] 71 [k3] 72 [k4] 73 [k5] 74 [k6] 75 [k7]

;; hardware regs used 7 [sp]

;; regular block artificial uses 7 [sp]

;; eh block artificial uses 7 [sp] 16 [argp]

;; entry block defs 0 [ax] 1 [dx] 2 [cx] 4 [si] 5 [di] 7 [sp] 20 [xmm0] 21 [xmm1] 22 [xmm2] 23 [xmm3] 24 [xmm4] 25 [xmm5] 26 [xmm6] 27 [xmm7] 36 [r8] 37 [r9]

;; exit block uses 0 [ax] 7 [sp]

;; regs ever live 0 [ax] 1 [dx] 2 [cx] 4 [si] 5 [di] 17 [flags]

;; ref usage r0={4d,5u} r1={2d,3u} r2={1d,1u} r4={2d,3u} r5={1d,1u} r7={1d,4u} r17={5d,1u} r20={1d} r21={1d} r22={1d} r23={1d} r24={1d} r25={1d} r26={1d} r27={1d} r36={1d} r37={1d}

;; total ref usage 44{26d,18u,0e} in 11{11 regular + 0 call} insns.

(note 1 0 7 NOTE_INSN_DELETED)

(note 7 1 48 2 [bb 2] NOTE_INSN_BASIC_BLOCK)

(note 48 7 2 2 NOTE_INSN_PROLOGUE_END)

(note 2 48 6 2 NOTE_INSN_DELETED)

(note 6 2 5 2 NOTE_INSN_FUNCTION_BEG)

(insn:TI 5 6 9 2 (set (reg/v:SI 0 ax [orig:88 d ] [88])

(reg:SI 2 cx [97])) "test.c":2:1 67 {*movsi_internal}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg:SI 2 cx [97])

(nil)))

(insn 9 5 10 2 (set (reg:CCZ 17 flags)

(compare:CCZ (reg:SI 5 di [94])

(const_int 0 [0]))) "test.c":3:6 7 {*cmpsi_ccno_1}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg:SI 5 di [94])

(nil)))

(jump_insn 10 9 11 2 (set (pc)

(if_then_else (eq (reg:CCZ 17 flags)

(const_int 0 [0]))

(label_ref 16)

(pc))) "test.c":3:6 736 {*jcc}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg:CCZ 17 flags)

(int_list:REG_BR_PROB 536870916 (nil)))

-> 16)

(note 11 10 12 3 [bb 3] NOTE_INSN_BASIC_BLOCK)

(insn:TI 12 11 13 3 (parallel [

(set (reg:SI 4 si [89])

(minus:SI (reg/v:SI 4 si [orig:86 b ] [86])

(reg/v:SI 1 dx [orig:87 c ] [87])))

(clobber (reg:CC 17 flags))

]) "test.c":4:15 254 {*subsi_1}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg/v:SI 1 dx [orig:87 c ] [87])

(expr_list:REG_UNUSED (reg:CC 17 flags)

(nil))))

(insn:TI 13 12 52 3 (parallel [

(set (reg:SI 0 ax [orig:84 <retval> ] [84])

(mult:SI (reg/v:SI 0 ax [orig:88 d ] [88])

(reg:SI 4 si [89])))

(clobber (reg:CC 17 flags))

]) "test.c":4:20 378 {*mulsi3_1}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg:SI 4 si [89])

(expr_list:REG_UNUSED (reg:CC 17 flags)

(nil))))

(insn 52 13 45 3 (use (reg/i:SI 0 ax)) -1

(nil))

(jump_insn:TI 45 52 46 3 (simple_return) "test.c":4:20 767 {simple_return_internal}

(nil)

-> simple_return)

(barrier 46 45 16)

(code_label 16 46 17 4 2 (nil) [1 uses])

(note 17 16 18 4 [bb 4] NOTE_INSN_BASIC_BLOCK)

(insn:TI 18 17 19 4 (parallel [

(set (reg:SI 1 dx [90])

(minus:SI (reg/v:SI 1 dx [orig:87 c ] [87])

(reg/v:SI 4 si [orig:86 b ] [86])))

(clobber (reg:CC 17 flags))

]) "test.c":6:15 254 {*subsi_1}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg/v:SI 4 si [orig:86 b ] [86])

(expr_list:REG_UNUSED (reg:CC 17 flags)

(nil))))

(insn:TI 19 18 26 4 (parallel [

(set (reg:SI 0 ax [orig:84 <retval> ] [84])

(mult:SI (reg/v:SI 0 ax [orig:88 d ] [88])

(reg:SI 1 dx [90])))

(clobber (reg:CC 17 flags))

]) "test.c":6:20 378 {*mulsi3_1}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg:SI 1 dx [90])

(expr_list:REG_UNUSED (reg:CC 17 flags)

(nil))))

(insn 26 19 55 4 (use (reg/i:SI 0 ax)) "test.c":7:1 -1

(nil))

(note 55 26 50 4 NOTE_INSN_EPILOGUE_BEG)

(jump_insn:TI 50 55 51 4 (simple_return) "test.c":7:1 767 {simple_return_internal}

(nil)

-> simple_return)

(barrier 51 50 47)

(note 47 51 0 NOTE_INSN_DELETED)

There isn’t a corresponding .dot dump file, as by this point

the CFG has been flattened away into a stream of instructions.

There’s a fairly direct correspondence between the above and the

generated assembler file, although you have to know a bit about RTL to

see it. For example if we just look at the insn instructions, we

can see that e.g. the final multiply instruction above:

(insn:TI 19 18 26 4 (parallel [

(set (reg:SI 0 ax [orig:84 <retval> ] [84])

(mult:SI (reg/v:SI 0 ax [orig:88 d ] [88])

(reg:SI 1 dx [90])))

(clobber (reg:CC 17 flags))

]) "test.c":6:20 378 {*mulsi3_1}

(expr_list:REG_DEAD (reg:SI 1 dx [90])

(expr_list:REG_UNUSED (reg:CC 17 flags)

(nil))))

i.e. “set %eax to the result of multipying %eax and %edx, clobbering the CC register” becomes:

imull %edx, %eax # tmp90, <retval>

in the output test.s assembler file.